In 2020, 9.7% of Housing Was Vacant, Down From 11.4% in 2010

The 2020 Census counted people where they were on April 1 of that year but it also counted where they were not.

The decennial census collects information on both vacant and occupied housing units and 2020 Census data released this week show a decline in the national vacancy rate. The percent of housing units that were vacant went from 11.4% in 2010 to 9.7% in 2020 but remained slightly higher than it was in 2000 (9.0%).

The states with the largest drop in vacancies from 2010 to 2020 were Nevada (14.3% to 8.1%), Arizona (16.3% to 12.2%) and Florida (17.5% to 13.5%).

These fluctuations reflect the timing and consequences of the housing crisis and Great Recession of the late 2000s. For many areas of the country, the economic downturn led to sharp vacancy rate increases between the 2000 Census and 2010 Census, followed by decreases between 2010 and 2020 as housing markets recovered.

Housing units are classified as vacant if no one was living in them on Census Day (April 1) — unless the occupants are absent only temporarily, such as away on vacation, in the hospital for a short stay, or on a business trip.

They are also classified as vacant if they are temporarily occupied entirely by individuals who have a usual residence elsewhere at the time of enumeration such as beach houses rented to vacationers who have a usual residence elsewhere.

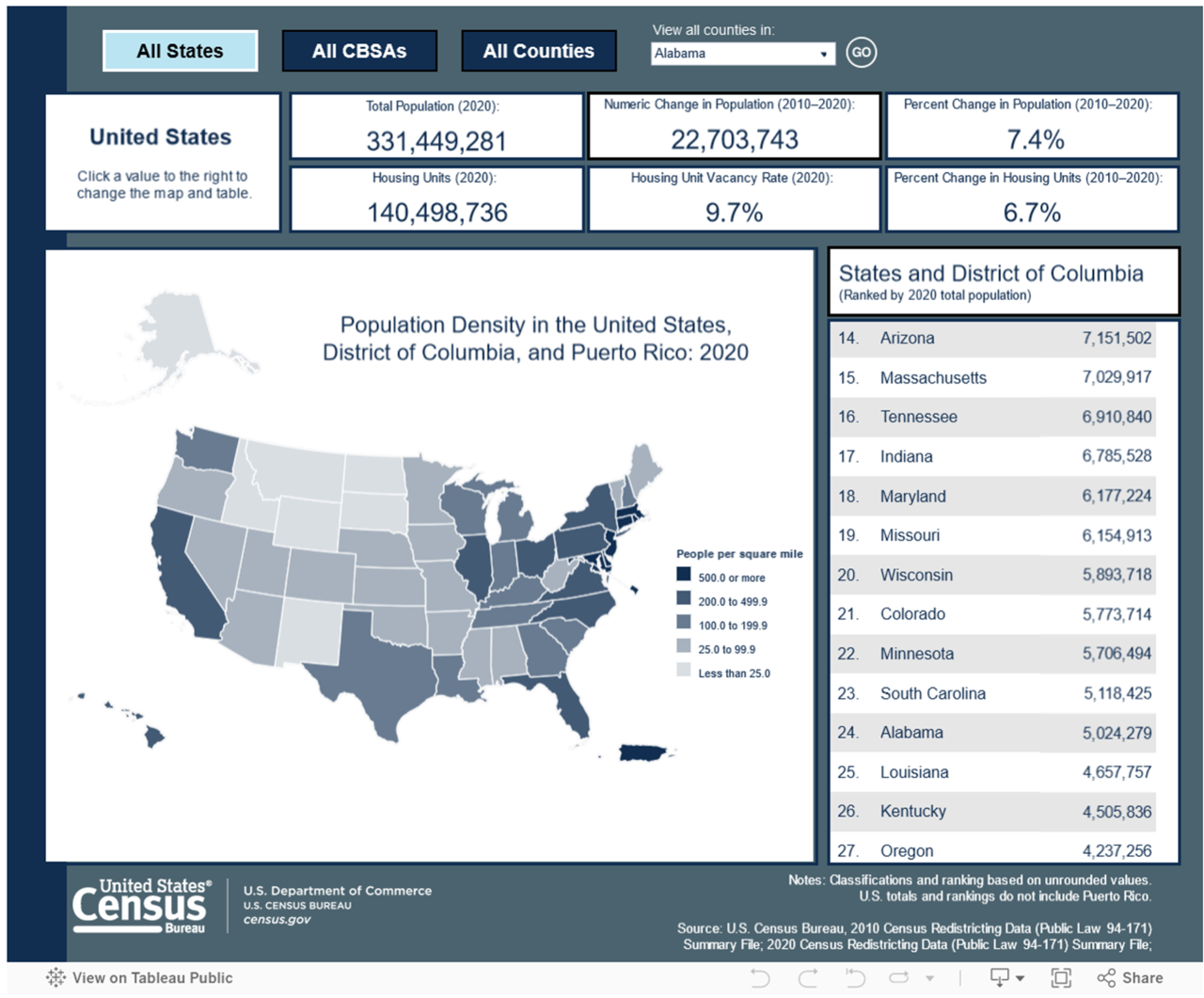

Data Visualization

Note: Select the image to go to the interactive data visualization.

High Vacancy Rates in Some States

States with the highest vacancy rates in 2020 were Maine (21.2%), Vermont (18.7%), and Alaska (17.5%) (Figure 1). Alaska was the only one of the three where housing vacancy increased over the last decade.

States that saw the greatest decline in their vacancy rates were located in the “Sunbelt,” which comprises most of the southern and southwestern states.

The states with the largest drop in vacancies from 2010 to 2020 were Nevada (14.3% to 8.1%), Arizona (16.3% to 12.2%) and Florida (17.5% to 13.5%).

Each of these states also had a rate of growth in housing unit counts that was slightly above the national average and had some of the highest growth in occupied housing units in the country.

Not all areas, including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, saw a decrease in their vacancy rate from 2010.

Aside from Alaska, which had the nation’s third-highest vacancy rate and biggest increase (1.6 percentage points), these states, or state equivalents, saw an increase in housing vacancy: North Dakota (1.5 percentage points); the District of Columbia (0.7 percentage points); Hawaii (0.3 percentage points); and Wyoming, Puerto Rico and Iowa (0.2 percentage points).

While there were increases, many of these states had vacancy rates in 2020 that were close to their 2000 and 2010 rates, indicating that their vacancy rates remained relatively stable. Even in Alaska and North Dakota, the states with two of the largest increases, increases were much smaller than the sizeable vacancy rate decreases Nevada, Arizona and Florida experienced.

How to Access, Download and Visualize Redistricting Data

Get tips and tricks on how to access, visualize and use Census Bureau data. The Census Academy team of data experts created these Data Gems.

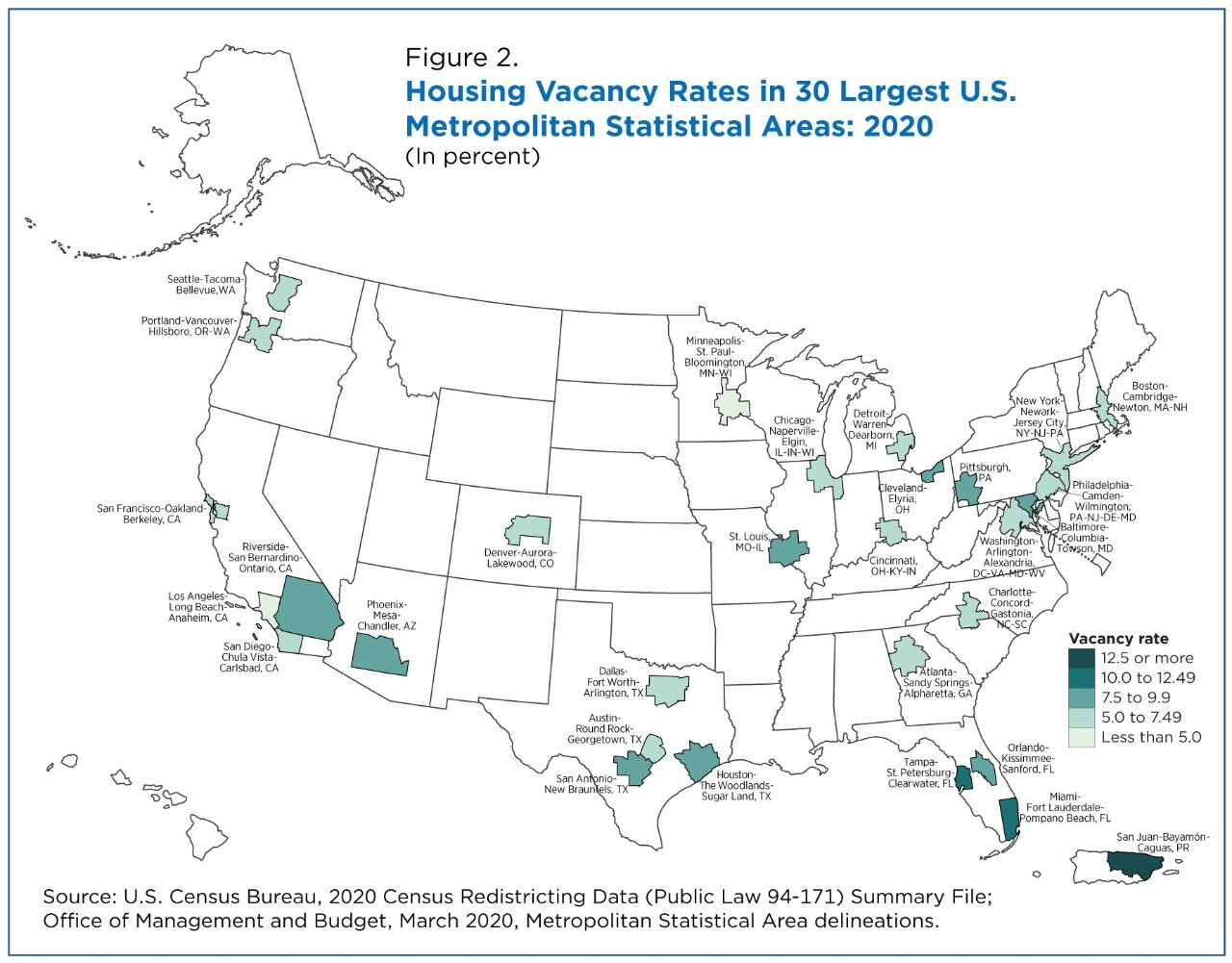

Vacancy Differs for Metro Areas Across the Country

As the state-level trends illustrate, not all areas of the United States experienced the housing crisis, Great Recession and subsequent recovery, in the same way. Core Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) — which comprise both metro and micro areas — show similar variations.

There are 939 CBSAs in the United States and Puerto Rico, which vary in size and consist of unique combinations of counties with very specific economies.

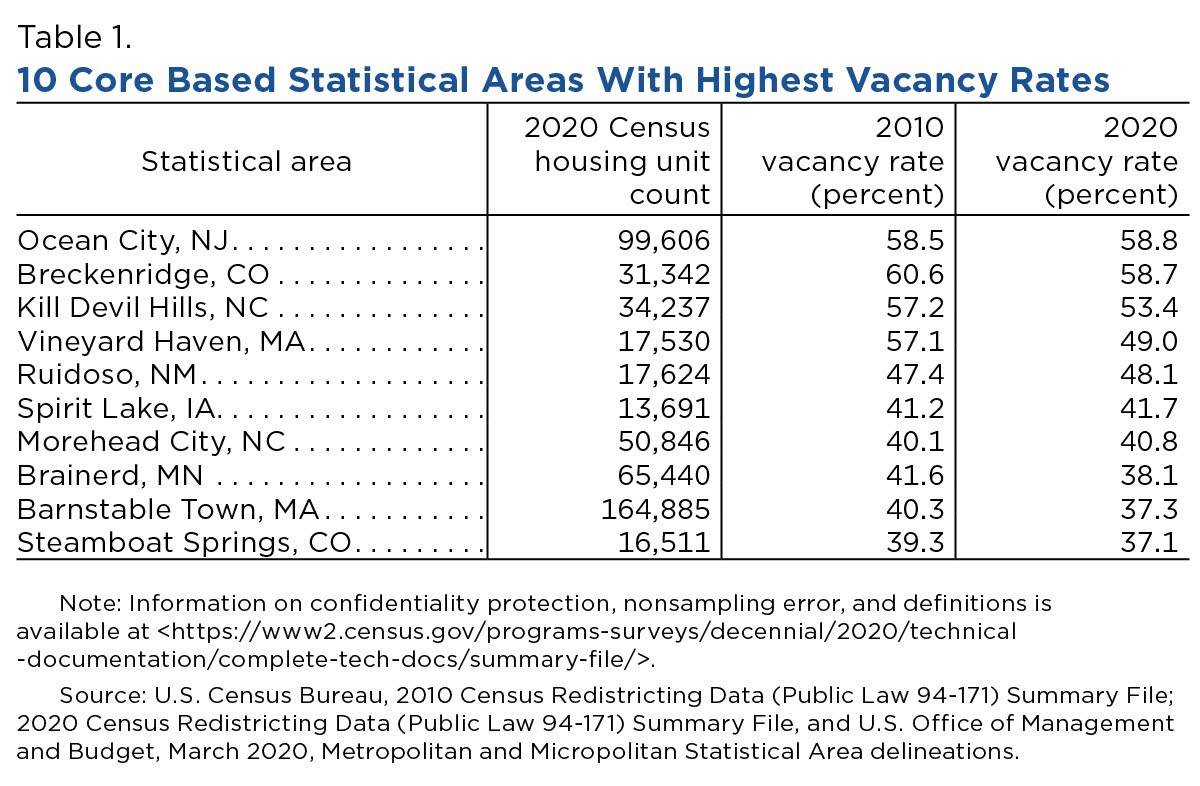

For example, beach towns or ski resorts, such as Ocean City, NJ, Kill Devil Hills, NC, and Breckenridge, CO, have many housing units that are seasonal or vacation rentals. It is not surprising then to see these vacation destinations on the list of CBSAs with the highest vacancy rates, some over 50% (Table 1).

Lower Vacancy in Large Metros

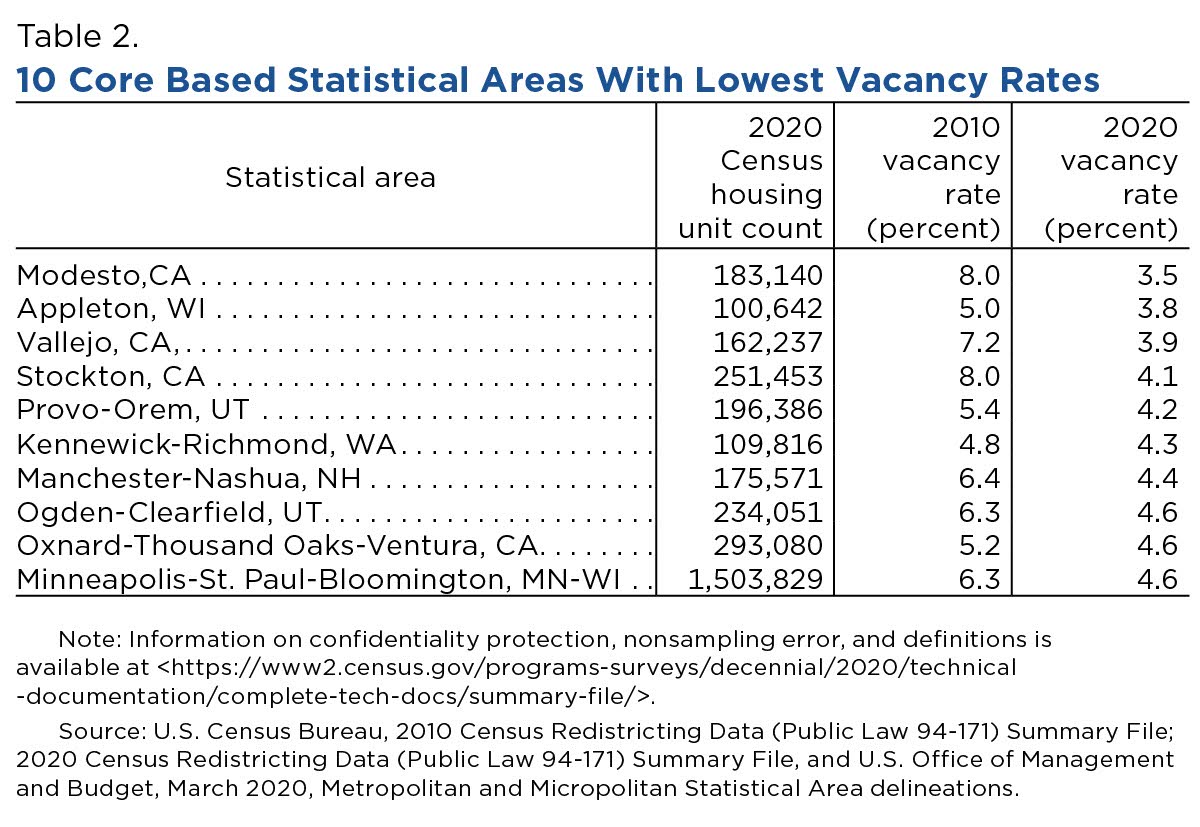

For the most part, the largest metropolitan areas had lower vacancy rates than the nation as a whole (Table 2).

Among the 30 largest CBSAs, only four (Miami, Phoenix, Tampa and San Juan) had vacancy rates above the national rate of 9.7%.

Conversely, the lowest vacancy rates among the 30 largest CBSAs appeared in Minneapolis (4.6%), Los Angeles (4.8%), Seattle (5.2%) and Portland (5.2%).

Among the largest 30 metropolitan areas, all but one (San Juan) saw a decrease in vacancy rate.

Only 10 of the 100 largest CBSAs had increases in vacancy. Among the 100 smallest CBSAs, 53 had increases. And 309 of the nation’s 939 CBSAs (including Puerto Rico) had increases.

Housing Vacancy and Recovery

As the nation recovered from the Great Recession and the housing crisis, housing vacancy rates declined from the highs recorded in the 2010 Census.

Most states and many metro areas saw their vacancy rates decrease between 2010 and 2020. Surveys such as the Housing Vacancy Survey, American Community Survey and American Housing Survey provide additional detail on how the housing stock changed between 2010 and 2020 — and will provide critical information about how these trends evolve this decade.

Related Statistics

-

2020 Census Decade: About the 2020 CensusHere is an overview of the 2020 Decennial Census.

-

Redistricting Data ProgramPublic Law 94-171 requires the Census to provide state legislatures with the small area census population tabulations necessary for legislative redistricting.

-

Housing Vacancies and Homeownership (CPS/HVS)Provides current information on the rental and homeowner vacancy rates, and characteristics of units available for occupancy.

-

American Community Survey (ACS)The American Community Survey is the premier source for information about America's changing population, housing and workforce.

-

American Housing Survey (AHS)The AHS is sponsored by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

-

America Counts: 2020 Census StoriesSee all stories on the 2020 Census, from data collection and promotion to the results of the decennial count that give us a complete portrait of America.

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

PopulationImproved Race, Ethnicity Measures Show U.S. is More MultiracialAugust 12, 2021Today’s release of 2020 Census data provides a new snapshot of the racial and ethnic composition of the country.

-

Population2020 U.S. Population More Racially, Ethnically Diverse Than in 2010August 12, 20212020 Census results released today allow us to measure the nation’s racial and ethnic diversity and how it varies at different geographic levels.

-

PopulationMore Than Half of U.S. Counties Were Smaller in 2020 Than in 2010August 12, 2021The U.S. Census Bureau today released the first 2020 Census population counts for counties, metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas, and cities.

-

PopulationWhat Do We Know About the Quality of 2020 Census Redistricting Data?August 12, 2021To assess the quality of the redistricting data released today, we compared 2020 Census to key data benchmarks.

-

PopulationWhich States Had the Highest Shares of Newcomers?April 29, 2025Many states with the highest share of recent movers from out-of-state in 2023 had relatively small populations.

-

Business and EconomyEntertainment, Travel, and Recreation Industries ReboundingApril 23, 2025A look at which selected travel, entertainment and recreation-related industries hit hard by the pandemic rebounded.

-

Income and PovertyNew Snapshots From the Survey of Income and Program ParticipationApril 21, 2025New Census Bureau product offers mobile-friendly fact sheets on who receives income from various sources.

-

PopulationU.S. Metro Areas Experienced Population Growth Between 2023 and 2024April 17, 2025New Census Bureau population estimates show 88% of U.S. metro areas gained population between 2023 and 2024.