How Does Growing Up in Assisted Housing Affect Adult Earnings?

How Does Growing Up in Assisted Housing Affect Adult Earnings?

In 2000, nearly 3 million children under age 18 lived in voucher-supported or public housing sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Although assisted housing programs have been in place for some time, research on the long-term effects on resident children is scarce and hampered by methodological limitations. To shed light on this topic, my colleagues and I combined Census Bureau data with administrative data to track children through assisted housing and into the labor force as adults.

The Census Bureau often combines survey and administrative datasets to produce new statistics, but these data can also help answer complex research questions. For this project, we identify families with multiple teenage children counted in the 2000 Census and link them to HUD administrative records to observe how they move into and out of assisted housing between 1997 and 2005. We then match the children to their adult earnings from 2011 to 2013 using data from the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program.

To identify the impact of assisted housing on earnings, we compare adult earnings between siblings who experienced different amounts of assisted housing as teenagers. As siblings share many of the background characteristics that affect adult earnings — for example, household poverty and parental motivation — we are able to distinguish the effect of assisted housing participation from the effect of any other shared childhood experiences.

We also look at whether public and voucher housing might have different effects on boys and girls. In public housing, a household lives in a project run by the local housing authorities, whereas in voucher-based housing, the housing authority pays a large portion of a household’s rent and utilities in private housing chosen by the household.

We first observe that children growing up in assisted housing tend to have lower adult earnings compared with other children, even those from similarly low-earning households. However, observing a difference in adult earnings between children who participated in assisted housing and those who did not is not enough to conclude that the assisted housing participation caused the difference. For example, participating households are required to earn below specified thresholds in order to be eligible. Beneficiary children are therefore likely to come from impoverished backgrounds and — even in the absence of assisted housing participation — earn less as adults.

When we use only between-sibling differences, we find that assisted housing participation is associated with increases in adult earnings for girls and only modest, often statistically insignificant, decreases in earnings for boys. In other words, holding constant family characteristics, the negative effect of assisted housing disappears for most children.

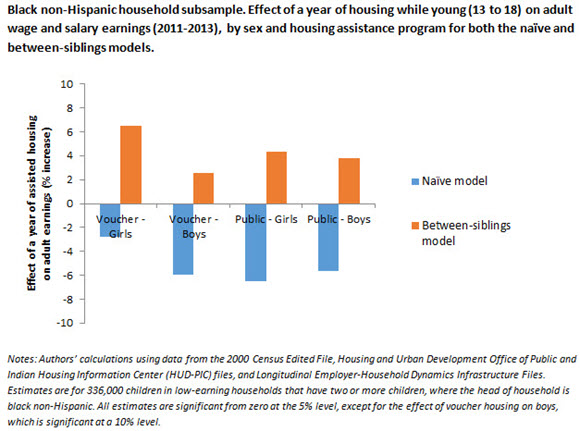

The overall result that assisted housing raises earnings for girls more than boys might depend on the community under study. To shed additional light on this difference, we look at results separately for white, black and Hispanic households. The between-siblings effects are consistently positive only for black non-Hispanics, who represent roughly half of all HUD residents (and are mostly not distinguishable from zero effect for whites and Hispanics). The figure below shows both the between-siblings estimates and the naïve estimates, those that do not compare siblings, for black non-Hispanic households.

In the between-siblings model, girls in black non-Hispanic households earn 6.5 percent more for each year spent in voucher housing and 4.3 percent more for each year spent in public housing while a teenager. Boys in black non-Hispanic households earn 2.6 percent more for each year they spent in voucher housing and 3.8 percent more for each year spent in public housing. The difference in the effects of voucher housing for girls in black non-Hispanic households relative to boys is statistically significant.

How might housing assistance affect children? While housing assistance relieves families of a major expenditure, other studies have shown that it may also concentrate low-earning households together in large public housing buildings or low-income neighborhoods, exposing children to high-poverty settings. Thus, the net effects are not certain without an empirical analysis. When distinguishing between the effects of assisted housing programs and family characteristics, we found that more time spent in assisted housing participation for siblings led to increases in adult earnings, especially for black non-Hispanic girls.

We are doing more research to try to unravel what aspects of housing assistance might have the greatest effects and to explore other adult outcomes that may be influenced by housing. We are also trying to understand why we observe girls benefiting more than boys for any type of housing assistance.

For more information, see Childhood Housing and Adult Earnings: A Between-Siblings Analysis of Housing Vouchers and Public Housing [PDF <1.0 MB], a joint paper written by Fredrik Andersson, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; John C. Haltiwanger, University of Maryland and U.S. Census Bureau; Mark J. Kutzbach, U.S. Census Bureau; Giordano Palloni, International Food Policy Research Institute; Henry O. Pollakowski, Harvard University; and Daniel H. Weinberg, Virginia Tech.