Using the Survey of Income and Program Participation to Study Residential Mobility

Using the Survey of Income and Program Participation to Study Residential Mobility

Considerable research has been devoted to understanding why households move. The generally accepted model of residential mobility suggests that moving is a process that begins with a mismatch between current housing and housing needs and aspirations. This mismatch leads to residential dissatisfaction, which in turn is associated with the desire to move and an actual move. However, despite wide acceptance of this model, our research and outside empirical tests have provided mixed results. In other words, households frequently do not move, even after expressing residential dissatisfaction and the desire to move.

The main difficulty with studying residential mobility is that few data sets combine longitudinal data on moves with measures of residential satisfaction and detailed characteristics of respondents and their residences. In a new report, titled Desire to Move and Residential Mobility: 2010 to 2011, I demonstrate how the Survey of Income and Program Participation, a current source of longitudinal data on migration, can be used to study residential mobility.

I combine longitudinal data on the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of householders, including demographic events and changes in job status, with topical module data (asked at only one or two time points) on residential satisfaction, self-reported home equity, and disability status to study residential mobility. I also utilize internal data on respondents’ census track of residence to look at relationships between neighborhood characteristics and residential mobility.

I first looked at how many people desire to move because of dissatisfaction with their current residence and the relationships between the various sets of predictor variables and householders’ reports of desiring to move. I found that in 2010, nearly one in 10 American households (9.6 percent) reported that they were dissatisfied enough with their current housing, neighborhood, local safety or public services that they desired to move.

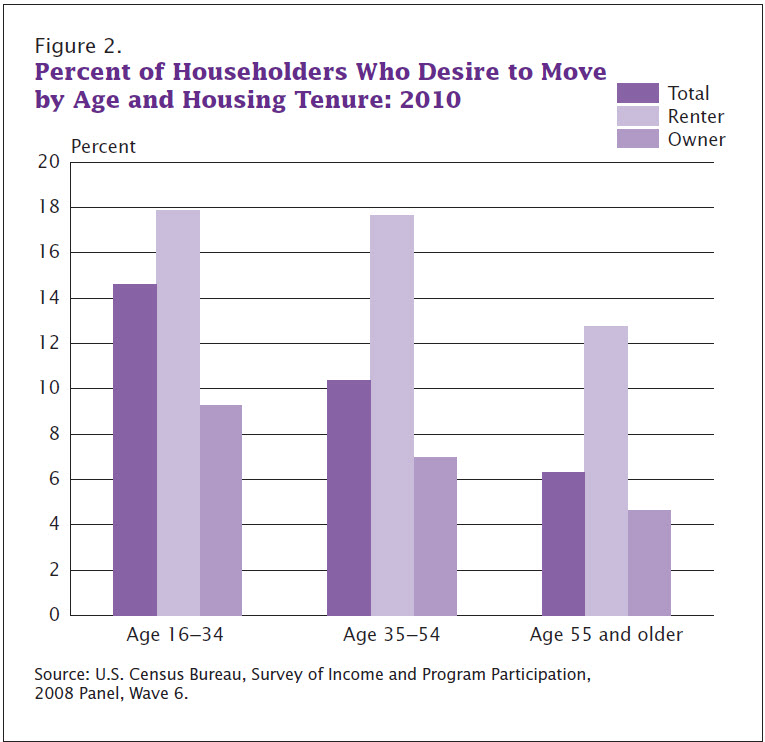

My research observed many expected relationships between the demographic and socio-economic predictors. Those who were younger and had lower income were more likely to desire to move. Renters were also more likely to desire to move than homeowners were.

Thanks to the richness of survey data, I was able to move beyond exploring relationships between basic demographics and desire to move. I found that demographic events, including having a child and getting married during the prior year, were associated with desiring to move. Disability status, in particular having a mental disability, was associated with desiring to move, as were neighborhood poverty levels and racial composition.

I next used the longitudinal design of the survey to see how many householders who reported desiring to move actually moved in the following year. I found that the majority of those who desired to move did not move within the next year, but their rate of moving was higher than that of the general population (18.3 percent compared with 9.6 percent). Consistent with past research on tenure status and mobility, renters who desired to move, moved at significantly higher rates than homeowners who desired to move. However, there was also some evidence the relationship between desiring to move and moving was stronger for homeowners. Homeowners who desired to move were almost twice as likely to move as the average homeowner (8.1 percent vs. 4.1 percent), but renters who desired to move were only about 1.2 times as likely to move as the average renter (25.4 percent vs. 20.8 percent). Also noteworthy, only 89,000 (5.3 percent) of the roughly 1.7 million homeowners age 55 and older who reported desiring to move actually moved in the following year.

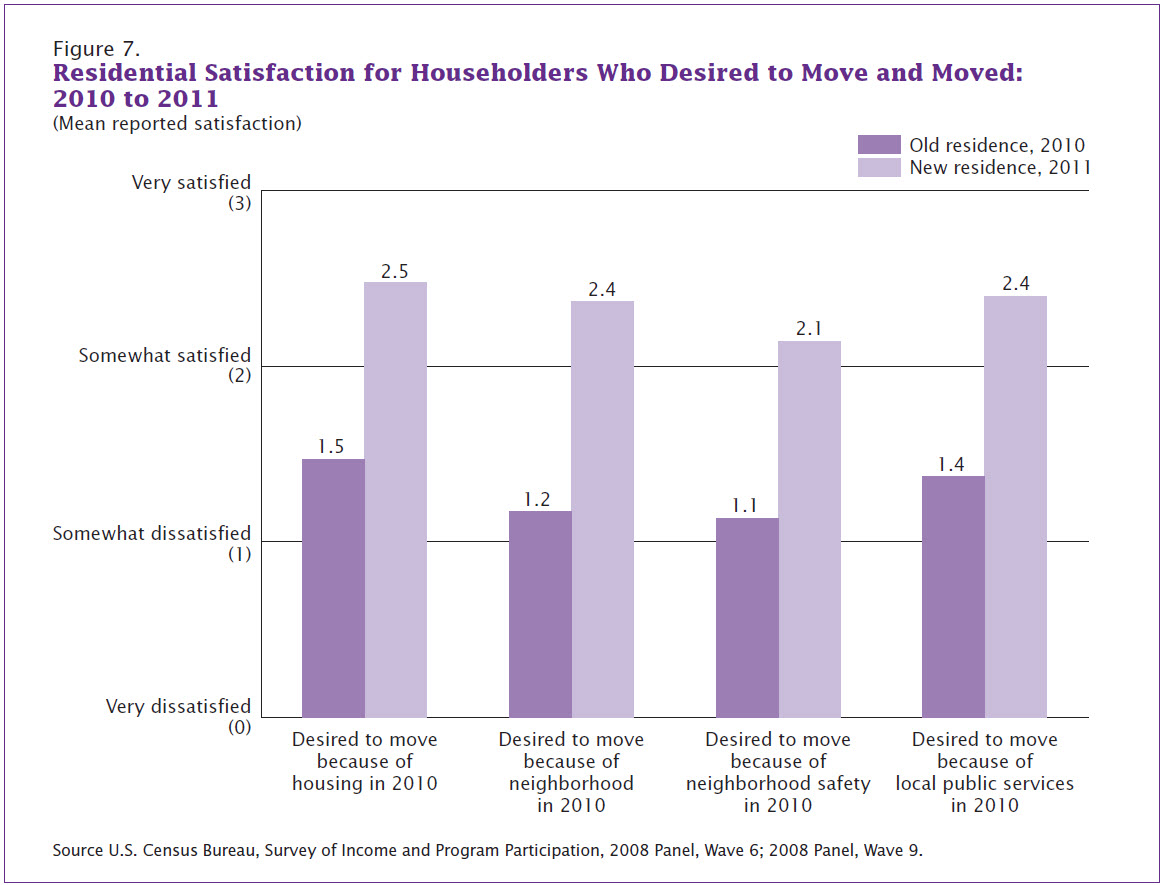

In the final portion of the report, I focused on how householders’ reports of residential satisfaction and desiring to move changed from 2010 to 2011. On average, householders who desired to move and moved from 2010 to 2011 reported greater residential satisfaction at their new residences compared with their old. However, the results also made it clear why a report of desiring to move may not always lead to a move, as many householders who desired to move in 2010 and did not move no longer reported desiring to move in 2011. This suggests another possible answer for why many empirical studies find that many people who report the desire or intention to move do not move; they change their minds. The reasons for these changes are for future analyses to untangle. However, this does not necessarily mean that these householders suddenly became happier with their residential circumstances. They may still be dissatisfied, just not to the extent that they desire to move.

Peter Mateyka, Analyst, Journey to Work and Migration Branch