An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock (

) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

-

//

- Census.gov /

- Newsroom /

- Census Blogs /

- Research Matters /

- The Early Evolution of Census Data Processing

From Tally Marks to Modern Computers — The Early Evolution of Census Data Processing

From Tally Marks to Modern Computers — The Early Evolution of Census Data Processing

When the nation counted 3.9 million residents in the very first census in 1790, the sheer workload of hand-tabulating the results was one of the founders’ greatest challenges. As the nation grew, so did the challenge. And when counting the results of the census took almost as long as the decade itself, the search for solutions ultimately led to the creation of modern data processing technology.

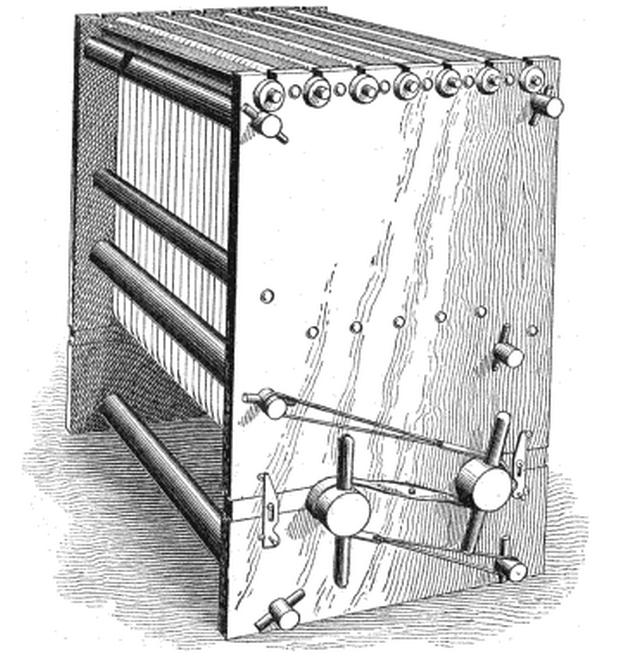

In 1888 the Census held a competition to find a more efficient way to process and tabulate data. Herman Hollerith’s electronic tabulator beat the competition, capturing and processing data by reading holes in punch cards. Census clerks could transfer the information on the census paper forms to punch cards, each creating about 500 punch cards a day. Variations on the Hollerith machine were used to process the 1890-1940 censuses.

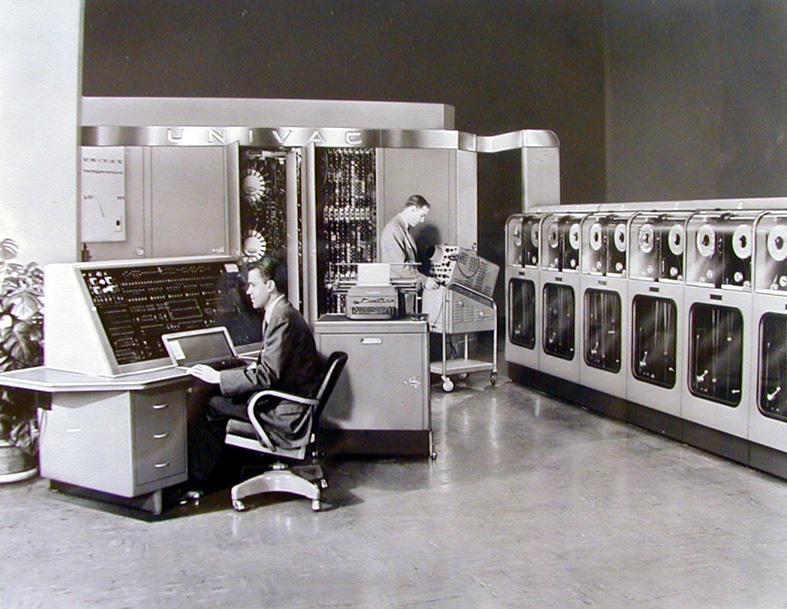

World War II and the military’s need for faster ballistics information processing led to the next big data processing advance. After the war, the focus shifted to peacetime applications of computers, and in 1951, the Census Bureau took delivery of UNIVAC, becoming the first civilian client of the modern digital computer. Built by the Eckert-Mauchley Computer Corporation at a cost of $400,000, UNIVAC processed data at a pace far outstripping the old Hollerith machines, with data entered using magnetic tape and processed using vacuum tubes with sophisticated circuits.

In this same decade Census engineers and staff at the National Bureau of Standards tackled the last big data processing hurdle – eliminating the need to transfer data to punch cards that could then be read by the computers. “Film Optical Sensing Device for Input to Computers,” or “FOSDIC,” made census forms machine-readable. The 1960 Census was the first to use the technology.

As Ruggles contended, advances in data processing up until the 1960s were driven by the growing challenge of processing the decennial census. See our next entry to learn how, from the 1960s and onward, the research community – increasingly equipped with modern computer technology – was the driving force behind revolutionary innovations in population data infrastructure and the expansion of the scale of all scientific data.

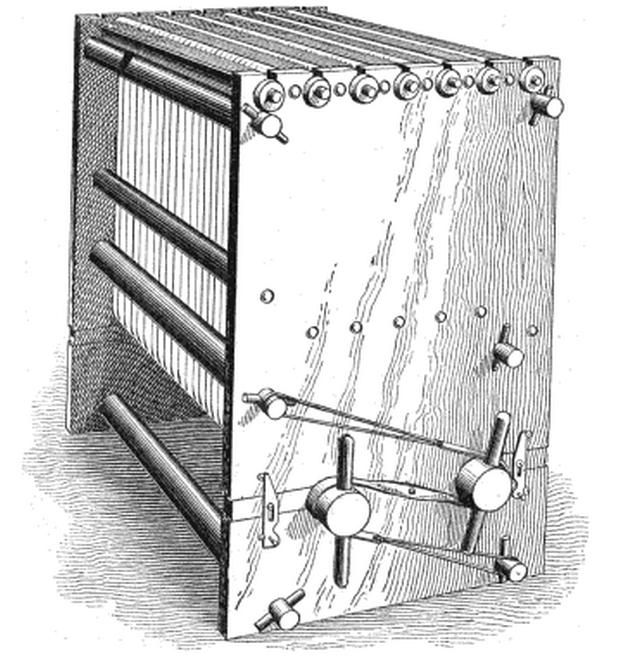

The Seaton Machine (1870-1880 Censuses)

The Hollerith Electronic Tabulator, 1902

Univac 1, 1952

Share

Yes

Yes

No

NoComments or suggestions?

Top