Improvements to the 2020 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Question Designs, Data Processing, and Coding Procedures

Improvements to the 2020 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Question Designs, Data Processing, and Coding Procedures

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

The U.S. Census Bureau has collected data on race since the first census in 1790 and on Hispanic or Latino origin (referred to as Hispanic origin in this blog) since the 1970 Census. How these topics are measured, and statistics on them are collected and coded, has changed nearly every decade throughout the history of the census, reflecting social, political and economic factors.

This blog discusses how we improved the census questions on race and Hispanic origin, also known as ethnicity, between 2010 and 2020. These changes provide important context as we prepare to release the 2020 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File.

The redistricting data will provide the first statistics on race and Hispanic origin from the 2020 Census. We expect the data will reflect not just changes in the population, but also the improvements in how we asked the questions and captured and coded the responses.

The Designs of the Questions

It is important to note that the Census Bureau collects race and ethnicity data in accordance with the 1997 Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity directed by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Therefore, the designs of the 2020 Census questions on Hispanic origin and race are similar to the designs used in the 2000 and 2010 censuses.

While the Census Bureau tested alternative question designs in 2015, we must ultimately follow the 1997 OMB standards and therefore used two separate questions to collect data on race and ethnicity. Our testing however did show that we could make improvements to the 2020 Census race and ethnicity questions within the OMB guidelines.

So, building on extensive research and outreach with advisers and stakeholders over the past decade, we made several improvements to the questions for the 2020 Census. We also improved the ways the Census Bureau processes and codes the responses to these questions.

Improvements to the 2020 Census Hispanic Origin Question

The 2020 Census Hispanic origin question (Figure 1) included the same three detailed checkboxes that were included in the 2010 Census (“Mexican, Mexican Am., Chicano,” “Puerto Rican,” “Cuban”), along with a “Yes, another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin” checkbox. There were two changes to the 2020 Census Hispanic origin question.

- The instruction to “Print origin, for example” was revised to “Print, for example.” In our research, we found that this revised instruction allowed respondents to understand what the question was asking them to report, and it did not limit their write-in response by confusing the instructions with terms (e.g., origin) that mean different things to different people.

- The example groups were revised from “Argentinean, Colombian, Dominican, Nicaraguan, Salvadoran, Spaniard, and so on.” to “Salvadoran, Dominican, Colombian, Guatemalan, Spaniard, Ecuadorian, etc.” in order to represent the largest Hispanic origin population groups and the geographic diversity of the Hispanic or Latino category, as defined by OMB’s 1997 standards.

Design Improvements to the 2020 Census Race Question

We also made several design improvements to the race question for the 2020 Census (Figure 2) based on our research over the past decade.

- In response to community feedback over the past decade, we added dedicated write-in response areas and examples for the “White” and the “Black or African Am.” racial categories.

- We provided six example groups for each of the “White,” “Black or African American,” and “American Indian or Alaska Native” racial categories. These examples represent the largest population groups within each of the geographically diverse population groups of each race category, as defined by the 1997 OMB standards.

- Based on successful previous testing, the term “Negro” was removed from the 2020 Census by updating the category “Black, African Am., or Negro” to “Black or African Am.” on paper questionnaires and “Black or African American” on electronic instruments.

- We reordered detailed Asian and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander checkboxes by population size.

- We changed the checkbox category “Guamanian or Chamorro” to “Chamorro” based on research and positive stakeholder feedback.

- We updated the write-in instructions for the “Some Other Race” category to better solicit detailed reporting. The 2010 Census form included the instruction to “Print race,” but we updated the 2020 Census instruction to read “Print race or origin” to correspond with the overall question instruction to “Mark ☒ one or more boxes AND print origins.”

How Data on Hispanic Origin and Race Are Processed and Coded in the 2020 Census Compared to the 2010 Census

Coding is a process we use to assign numeric codes to write-in responses to the Hispanic origin and race questions, and we use the numeric codes when we process and tabulate the data. In the 2010 Census, we only captured the first 30 characters of written responses to the race and ethnicity questions and coded up to two write-in responses in each write-in line.

Our research found that people were reporting longer and more detailed responses to the questions. For the 2020 Census, we wanted to reflect more fully and accurately the complex details of how people identify their race and ethnicity.

Based on further research, testing and outreach throughout the decade, we changed how we captured and coded responses for the 2020 Census race and Hispanic origin questions:

- We increased the number of characters captured from 30 to 200, which allowed us to capture and fully recognize longer write-in responses.

- Instead of prioritizing multiple responses into only two codes, we coded up to six detailed codes for each write-in area. This increase effectively gave all responses an equal opportunity to be coded into one of the six major race categories. It also simplified our coding work that removed duplicate or repetitive terms to reduce responses to two codes.

We fully tested these coding and question changes in the 2015 National Content Test and finalized them in the 2018 Census Test. We processed and coded the race and ethnicity data from the 2020 Census from April to December 2020.

The figures below illustrate how a response was coded in 2010 versus 2020, based on the differences described above.

Figure 3 shows that in the 2010 Census, the response of “MEXICAN AMERICAN INDIAN AND PORTUGUESE AND AFRICAN AMERICAN” was not fully coded because it was longer than 30 characters.

- Only the text outlined by the red box “MEXICAN AMERICAN INDIAN AND PO” was captured and coded in the 2010 Census.

- The additional text “RTUGUESE AND AFRICAN AMERICAN” was not captured.

- Portuguese and African American was not coded.

Figure 4 shows that if the same write-in response was provided in 2020, all of the text outlined by the red box was captured. This change enabled all three terms of “MEXICAN AMERICAN INDIAN AND PORTUGUESE AND AFRICAN AMERICAN” to be recognized and coded.

In another major improvement for the 2020 Census, we used a single code list for coding data from the Hispanic origin question and the race question.

In previous censuses, we used two separate code lists — one for the Hispanic origin question and one for the race question. Previously, these code lists focused on providing codes for either detailed Hispanic groups or detailed race groups. By combining these code lists, we expanded the number of detailed groups that could be coded in each question.

For example, if someone reported their detailed Hispanic origin response in the race question, we were easily able to code it because all detailed Hispanic origin groups are included in the newly combined code list. Likewise, if they reported their detailed Asian response in the Hispanic origin question, we were easily able to code it because all detailed Asian groups are included in the combined code list.

We also expanded our code list to include additional detailed White and Black or African American groups as the race question purposefully elicited the collection of detailed White and Black or African American responses through dedicated write-in lines for the first time.

The 2020 Census Hispanic Origin and Race Code List is available online as part of the 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Technical Documentation, and illustrates the extensive codes added for 2020 to enable the coding of responses for all racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

Coding Improvements to the 2020 Census Hispanic Origin Question

During the 2010 Census, if someone provided more than two write-in responses in the Hispanic origin question write-in area, we prioritized coding Hispanic groups over race groups or other types of responses.

In the 2020 Census, subject-matter experts coded what they saw, coding up to six responses from left to right, regardless of the Hispanic origin or race group. This enabled all responses to be treated equally. Table 1 illustrates this coding change.

After coding up to six responses on the Hispanic origin question write-in line, like the 2010 Census and previous censuses, only one response is permitted to be tabulated for Hispanic origin in accordance with the 1997 OMB standards.

In Figure 5, we can see how this does not impact the Hispanic origin data for the redistricting data. In 2020, with the coding improvements, we code all three responses of Black (as shown in the green text), Colombian and Peruvian. All of these codes are retained internally for research purposes.

For the official redistricting file tabulations, this response is tabulated as Hispanic or Latino. Following the 1997 OMB standards, respondents can only be Hispanic or Not Hispanic. As long as the respondent provides at least one Hispanic origin response, they are tabulated as Hispanic.

Coding Improvements to the 2020 Census Race Question

The 2010 Census used a complex series of coding rules to determine how to prioritize and assign up to two codes for each unique text string. In 2010, if more than two groups were part of a write-in text string on the same line in the race question, we prioritized coding race groups over Hispanic origin groups or other types of responses because we were limited to only coding two responses.

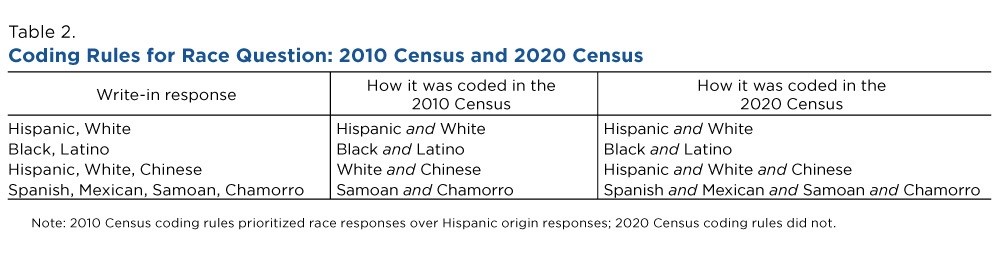

In the 2020 Census, our subject-matter experts coded what they saw, coding up to six responses from left to right, regardless of race group or Hispanic origin, enabling all responses to be treated equally. Table 2 illustrates this coding change.

In Figure 6, we can see how this improvement to the coding rules impacts our final data by recognizing the rich and complex detailed identities reported by respondents.

- In 2010, even though Cuban was written first (as shown in the green text), the responses of Thai and Filipino were prioritized over Cuban because they are detailed race groups.

- Cuban was not coded or included in race tabulations because the two race groups were prioritized over it in coding.

- This response was tabulated as part of the Asian race category (representing Thai and Filipino) in 2010.

- In 2020, all three groups in the write-in response are coded and the response would be tabulated as Asian and Some Other Race (representing Thai and Filipino, and Cuban). The 2020 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File tabulates major race groups (e.g., White, Black, Asian, etc.), so the responses of Thai and Filipino are included in the aggregate Asian racial category. Note, Hispanic responses to the race question are tabulated as part of the Some Other Race category, as Hispanic or Latino is not considered a race in the 1997 OMB standards.

Summary

Improving the 2020 Census questions on Hispanic origin and race, along with our coding procedures, enable us to have a more complete picture of the detailed identities reported by the U.S. population in 2020.

Because of the changes associated with questionnaire design, processing, and coding, users may see differences in the data when comparing to other Census Bureau surveys or non-Census Bureau data sources. If unexpected differences occur, this may be related to a number of factors, primarily the design of the race and ethnicity questions and the improvements to the ways in which we code what people tell us.

We expect that the race and Hispanic origin statistics in the upcoming redistricting data release will not only reflect demographic changes, but also improvements in how we asked the questions and captured and coded the responses.

These improvements more accurately illustrate the richness and complexity of how people identify their race and ethnicity in the 21st century.