Shift Toward Greater Educational Attainment for Women Began 20 Years Ago

Shift Toward Greater Educational Attainment for Women Began 20 Years Ago

Statistics from the American Community Survey show women now lead men in college completion (see Women Now at the Head of the Class, Lead Men in College Attainment). Colleges have been graduating more women than men for more than 20 years, but what is new is that the advantage is no longer limited to new graduates and young women. Counting the entire population 25 and older, even women and men who are retired, women are ahead of men in college graduation. That is to say, the average adult woman in the U.S. is more likely to be a college graduate than the average adult man.

In order to better understand this change, the report “Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015” assembles statistics on historical trends in men’s and women’s college graduation. The Current Population Survey has collected data on Americans’ educational attainment since 1967 and provides an unparalleled data set for looking at the education level of the population over a broad period of time.

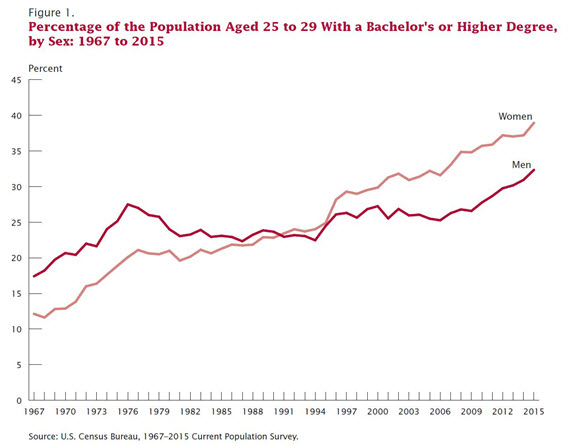

To look more closely at what is happening to education levels of women and men, it helps to look at trends among younger people. Women age 25 to 29 have had higher college attainment rates than men of the same age since 1996. This higher rate is not limited to women in the United States. Nearly all the countries with advanced economies that form the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report that young women are ahead of young men in college completion.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of men and women in the U.S. population age 25 to 29 who had completed a bachelor’s or higher degree. Before 1986, men had higher college completion; from 1996 forward, women were in the lead. Across the period, women had a fairly steady increase in college attainment, while men’s attainment has been more subject to ups and downs.

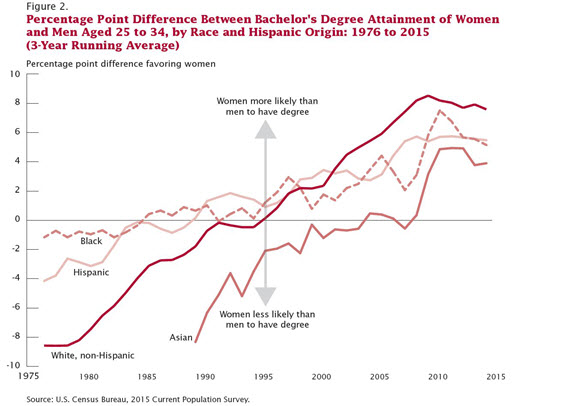

Looking at the broader 25- to 34-year-old group (because sample sizes by race, gender and age group become too small for precise estimates), the increase in college completion of women relative to men is seen in all major race and Hispanic-origin groups (Figure 2).

The figure shows the college attainment of women relative to men of this age range for each race and Hispanic-origin group — a rise in the curve showing an increase in women’s attainment compared with men. In the early part of the period shown here, from 1976 to 1989, a smaller portion of young non-Hispanic white women than young non-Hispanic white men had bachelor’s degrees. By contrast, in this period young black women were not statistically different from young black men. Other sources show that by some measures they were actually ahead. Young Hispanic women were somewhere in between, sometimes ahead of their male counterparts, sometimes not. Data on Asian women and men are not available for this period.

In 1990, young Asian women were less likely to have completed a bachelor’s than young Asian men, and the gap was larger than for blacks, non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics. After that point, a transition took place. By 2010, young women of all these race and Hispanic-origin groups were more likely to have completed college than their young male counterparts (all comparisons 2010 to 2015 are statistically significant except for Asians in 2012 and 2014).

Research on this topic has not given us a clear answer as to why women have overtaken men in college attainment. Traditionally, researchers have looked at levels of education as being driven by the resources available, especially from families, and by the rewards of education, particularly earnings and occupational standing. Most research has concluded that the rewards of education for men and women have not shifted over time in a way that explains women’s higher attainment. An exception is work by Bachman and DiPrete holding that women benefit from education as “insurance against poverty” in a time of increasing family instability. Even if rewards haven’t shifted, women’s gains might have resulted from changes in resources for education (family encouragement and educational practices) that once may have favored men. Increasing age at marriage may have also played a role. Reviews on this subject are available from Aliprantis et al (2011) and Buchman and DiPrete (2008).