Household Pulse Survey Shows 31.1% Reported Symptoms Three Months or Longer After They Had COVID-19

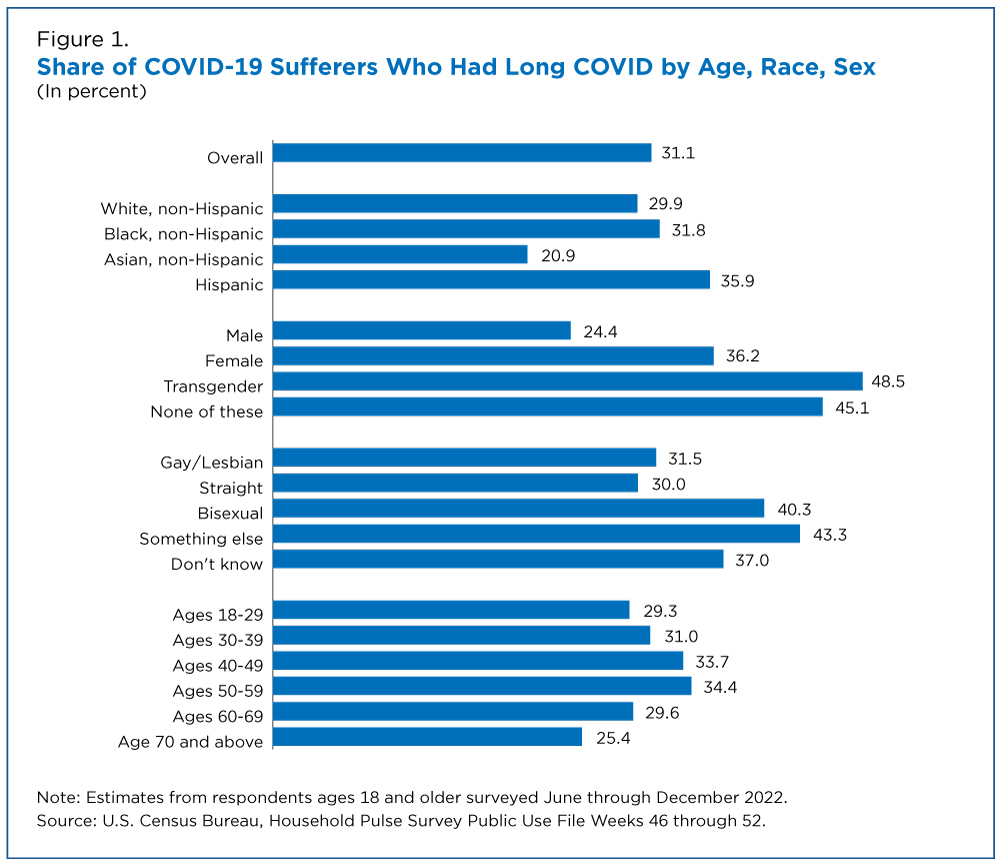

Hispanic and Black respondents were more likely than other racial or ethnic groups to report COVID-19 symptoms lasting three months or longer, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS).

The HPS, an experimental online survey representative of the U.S. adult population at the state and national level, began asking about long COVID symptoms in June of 2022, more than two years after the pandemic hit the United States. It found that 31.1% of respondents ages 18 and over reported long-lasting symptoms.

Findings are based on responses collected from June to December 2022. See the technical documentation for more information about the HPS.

Women were more likely than men to say they suffered long-lasting symptoms.

Respondents were asked if they had ever tested positive for or had been told by a health care provider they had COVID-19. Respondents who answered “yes” were then asked if they had symptoms they did not have pre-COVID-19 that they still experienced at least three months later.

The HPS data tool allows users to explore a number of different national, state and metro area estimates, including the percentage of adults who experienced long COVID symptoms.

This story delves deeper into the profile of long COVID sufferers and their overall well-being.

Who Suffers Long COVID?

Hispanic respondents were the most likely to report long COVID symptoms and non-Hispanic Asian respondents were the least likely (Figure 1).

Though less likely than Hispanic respondents, Black respondents were more likely than White or Asian respondents to suffer long COVID.

Women were more likely than men to say they suffered long-lasting symptoms.

People between ages 40 and 59 were the most likely to report long COVID symptoms, while those in the oldest age category (70 and over) were the least likely.

Does Long COVID Vary by Education and Income?

Respondents without a high school degree were the most likely to report long COVID symptoms while those with a college degree were the least likely (Figure 2).

Interestingly, those with a high school degree or less were the least likely to report having tested positive for COVID-19 while those with at least some college were the most likely (those with some college education were not significantly different from those with a college degree).

The HPS income question is categorical, so to avoid conflating different types of households the universe was limited to two-adult/two-children households.

Not all estimates were significantly different but it is clear that those at the top income distribution (more than $100,000) were less likely than those at the bottom (less than $100,000) to report long COVID.

Are Long COVID Sufferers Worse Off in Other Areas?

Now that we have a better understanding of who long COVID sufferers are, let’s review several measures of well-being.

First some definitions. A person faces financial insecurity if they respond that it had been very difficult for their household to pay for usual household expenses. They are in multidimensional hardship (MHI) if they reported at least two of the following:

- Mental health. Feeling down, depressed or hopeless more than half the days in the previous week.

- Job insecurity. Not being employed due to illness, caring for others or losing a job due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Food insufficiency. Living in a household that sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat in the last 7 days.

- Housing insecurity. Little or no confidence in their ability to make mortgage or rent payments the next month.

Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents who reported hardship in these well-being measures in each COVID-19 category: never had Covid-19; had COVID-19 and reported having long COVID symptoms; had COVID-19 and reported no long COVID symptoms.

Approximately 27% of long COVID sufferers were financially insecure, compared to 18% of people who never tested positive for COVID-19, and 15% of people who did but did not have long COVID symptoms. The overall pattern was the same for each measure. Respondents with long COVID symptoms reported the highest level of hardship defined by each measure.

Respondents reporting they never tested positive for COVID-19 actually faced higher levels of hardship than those who did test positive but reported no long-lasting symptoms.

Related Statistics

-

Household Pulse SurveyThe Household Pulse Survey is designed to deploy quickly and efficiently to measure how emergent social and economic issues are impacting U.S. households.

-

Data ToolCensus COVID-19 Data HubThis site provides users demographic risk factor variables along with economic data on 20 key industries impacted by Coronavirus.

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

America Counts StoryHow the Pandemic Affected Black and White HouseholdsJuly 21, 2021Loss of income during the pandemic caused more hardship for Black adults than for White adults, even after accounting for differences in income and education.

-

America Counts StoryHow Food Service, Transportation Workers Fared Before PandemicJuly 27, 2022A new U.S. Census Bureau report shows that people in some occupations hard hit during the pandemic had low earnings and benefits even before COVID-19.

-

America Counts StoryParents and Children Interacted More During COVID-19January 03, 2022During Covid-19 lockdowns, parents changed how they interacted with children: more dinners and reading together but fewer outings.

-

EmploymentThe Stories Behind Census Numbers in 2025December 22, 2025A year-end review of America Counts stories on everything from families and housing to business and income.

-

Families and Living ArrangementsMore First-Time Moms Live With an Unmarried PartnerDecember 16, 2025About a quarter of all first-time mothers were cohabiting at the time of childbirth in the early 2020s. College-educated moms were more likely to be married.

-

Business and EconomyState Governments Parlay Sports Betting Into Tax WindfallDecember 10, 2025Total state-level sports betting tax revenues has increased 382% since the third quarter of 2021, when data collection began.

-

EmploymentU.S. Workforce is Aging, Especially in Some FirmsDecember 02, 2025Firms in sectors like utilities and manufacturing and states like Maine are more likely to have a high share of workers over age 55.