Child Care Subsidies Help Married Moms Continue Working, Bring Greater Pay Equity

Federally funded child care subsidies may help working married mothers stay in the labor force and narrow the pay gap between spouses, according to a new U.S. Census Bureau working paper.

The study showed the subsidies increased the likelihood working married mothers would stay in the labor force after four years. It also suggests positive impacts on pay equity: subsidies helped these mothers earn a more equal share of their household’s total earnings.

The theory behind child care subsidies is simple: Provide working parents financial assistance to help pay for child care and they’ll be more likely to keep working.

The findings are based on data from the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), Social Security Administration (SSA) and the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS).

A Consistent Trend

Working mothers often carry more of the load when it comes to balancing work and family, as past research has shown.

As a result, working moms have borne the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic. Census data showed that of those not working, women ages 25-44 were nearly three times as likely as men not to work outside the home because of child care demands.

The cost of child care is the main challenge, especially for those in low-income, working-class populations. Paid child care is expensive in the United States, greatly reducing household take-home pay and potentially “pricing out” working married mothers from the labor market.

The theory behind child care subsidies is simple: Provide working parents financial assistance to help pay for child care and they’ll be more likely to keep working.

Labor Force Benefits

Researchers used unique data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and linked to CCDF administrative records and the Social Security Administration’s Detailed Earnings Records to analyze the impact of the program.

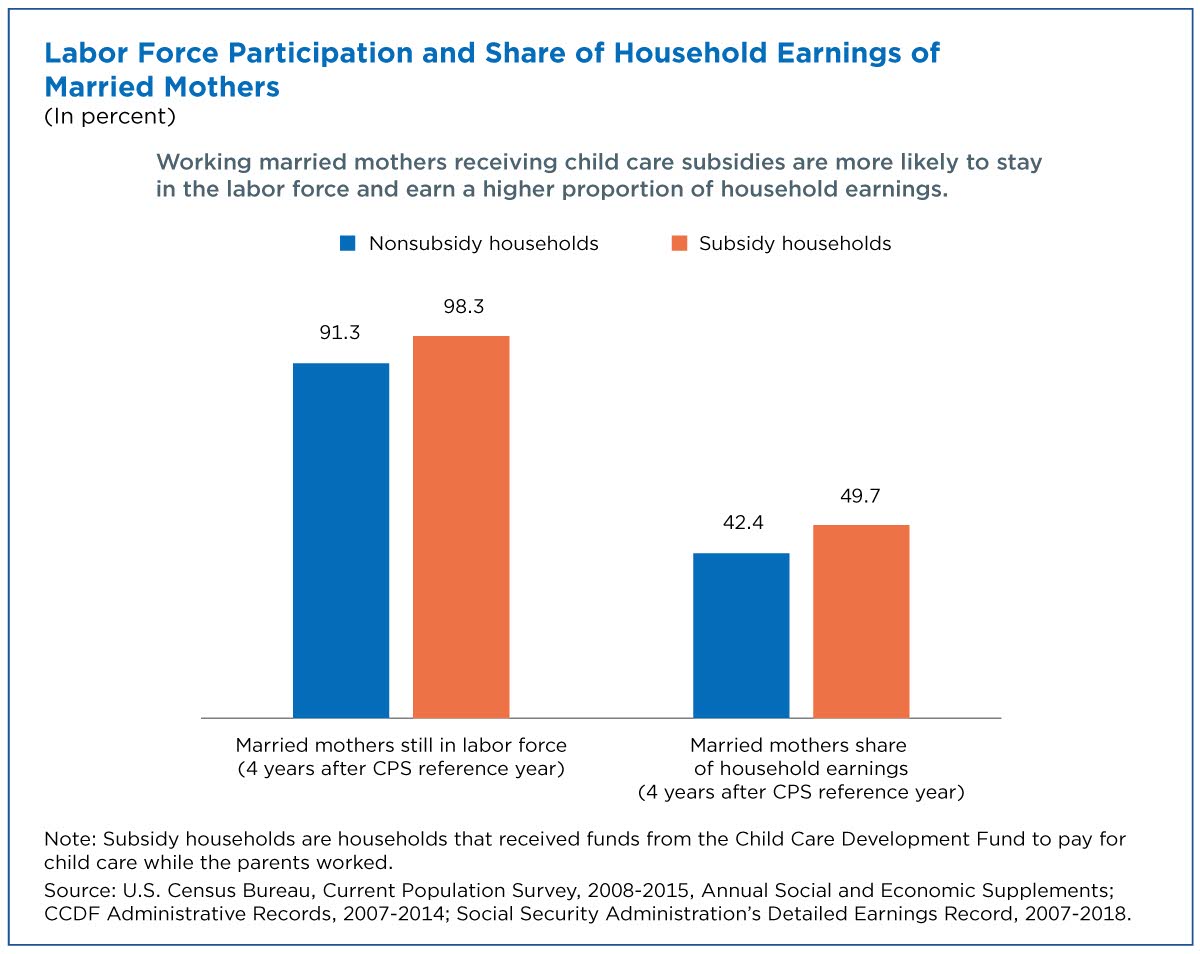

They found that 98.3% of subsidy-receiving married mothers who worked during the CPS reference year remained in the labor force four years later – compared with 91.3% of married mothers who worked the same year but did not receive a subsidy.

Mothers in CCDF households also had smaller wage differences from their working spouses four years later, earning a more equitable proportion of household income: 49.7% compared to 42.4% for those without CCDF.

What About Socio-Economic Differences?

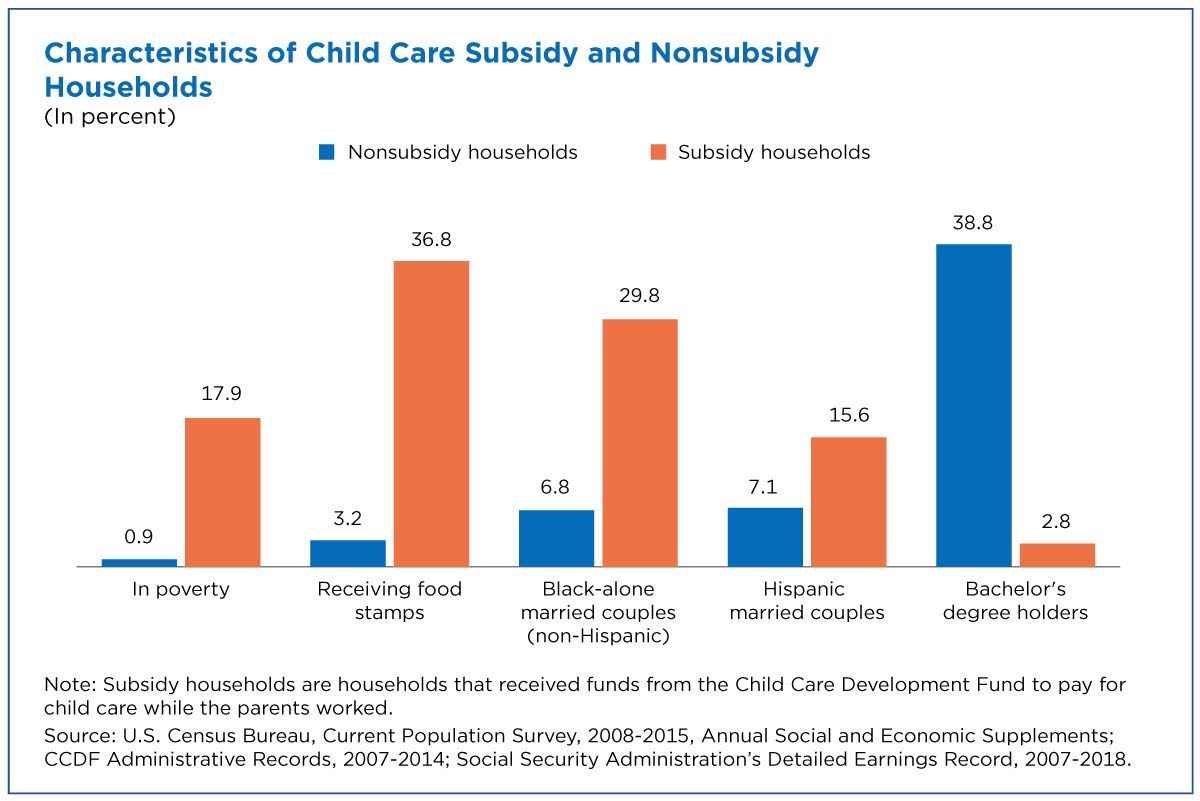

One challenge researchers faced is that CCDF is targeted at low-income populations with varied eligibility requirements across localities and time. Certain marginalized groups (non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and those without a college degree) are more likely to be CCDF recipients.

The study addressed this challenge by matching nonsubsidy and subsidy households with a similar likelihood of receiving CCDF based on key characteristics: income, race, education, locality, survey year and other family characteristics.

Even when adjusting for households with varying propensities to receive CCDF, child care subsidies improved labor force retention and reduced spousal wage gaps among working married mothers.

Given the data come from a variety of sources, all data in the study are subject to sampling error, nonsampling error, modeling error and other sources of error. Further information on data collection, statistical standards and accuracy are available on our technical documentation page.

Benjamin Gurrentz is a survey statistician in the Census Bureau’s Survey Improvement Research Branch.

Related Statistics

-

Stats for StoriesNational Child's Day: November 20, 2023In 2021, the majority (71%) of America’s 72.3M children under 18 lived with two parents and the next largest share (20.9%) lived with their mothers only.

-

Stats for StoriesEqual Pay Day: March 12, 2024In 1973, full-time working women earned a median of 56.6 cents to every dollar men earned. In 2022 (49 years later), women earned 84.0, a gain of 27.4 cents.

-

Stats for StoriesWomen’s Equality Day: August 26, 2023According to the Current Population Survey, 2020 voter turnout was 68.4% for women and 65.0% for men. About 9.7 million more women than men voted.

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

America Counts StoryParents Juggle Work and Child Care During PandemicAugust 18, 2020Working mothers of school-age children bore the brunt of stay-at-home orders, taking personal leave or juggling childcare while working extra hours.

-

America Counts StoryMoms, Work and the PandemicMarch 03, 2021New data show that there were 1.4 million more mothers not actively working for pay in January compared to pre-pandemic levels.

-

America Counts StoryUnequally Essential: Women and Gender Pay Gap During COVID-19March 23, 2021On the eve of Equal Pay Day and as the nation recognizes Women’s History Month, Census Bureau data show women still face pay disparities across occupations.

-

PopulationWhich States Had the Highest Shares of Newcomers?April 29, 2025Many states with the highest share of recent movers from out-of-state in 2023 had relatively small populations.

-

Business and EconomyEntertainment, Travel, and Recreation Industries ReboundingApril 23, 2025A look at which selected travel, entertainment and recreation-related industries hit hard by the pandemic rebounded.

-

Income and PovertyNew Snapshots From the Survey of Income and Program ParticipationApril 21, 2025New Census Bureau product offers mobile-friendly fact sheets on who receives income from various sources.

-

PopulationU.S. Metro Areas Experienced Population Growth Between 2023 and 2024April 17, 2025New Census Bureau population estimates show 88% of U.S. metro areas gained population between 2023 and 2024.